"How many stocks should I own?" is a common question I receive, so I decided to write up this article, as well as create a free spreadsheet to help you out with this dilemma.

Theoretically speaking, if your goal is to maximize your returns, and I assume that is your goal, your best idea, the one you expect to earn you the most money, should receive all your money.

But this type of "concentration" is deemed risky.

So you often hear about diversification and portfolio optimization to reduce the overall risk of your portfolio.

The risk of losing money that is.

Protecting the downside seems like a logical thing to do, since Buffett's #1 rule is to never lose money.

However, at some point you will not only lower the downside risk, but also lower the upside potential.

If you buy enough stocks, your returns will regress to the mean, and you would have been better off buying an index fund, as that would have saved you a lot of work and transaction costs.

Just six stocks

So what then is the ideal number of stocks you should own?

This is what Warren Buffett had to say about this in 1998:

If you can identify six wonderful businesses, that is all the diversification you need, and you’re going to make a lot of money, and I will guarantee you that going into a seventh one rather than putting more money in your first one is a terrible mistake.

Only six stocks?!

Yes, that is plenty.

It takes a lot of effort to identify wonderful businesses, and it is rare you get to buy one of them at a good price, so doing this 6 times is quite a feat, actually!

Business legend Andrew Carnegie seems to agree as well:

They have investments in this, or that, or the other, here, there and everywhere. “Don’t put all your eggs in one basket” is all wrong. I tell you “put all your eggs in one basket, and then watch that basket.” Look around you and take notice; men who do that do not often fail. It is easy to watch and carry the one basket.

And like Buffett said, aren't you much better off investing more money in your #1 best stock idea, rather than in your seventh best?

"But what if I have $1000 / $10.000 / $100.000 to invest?!"

The same thing holds true, regardless of how much money you have to invest, except that with $1000 I would suggest to invest in even less than six stocks, as the transaction costs would eat up a large chunk of your profits otherwise.

As Charlie Munger once said:

The wise ones bet heavily when the world offers them that opportunity. They bet big when they have the odds. And the rest of the time, they don't. It's just that simple.

So bet heavily when the opportunity arises.

Don't be afraid to have double digit % of your portfolio allocated to one stock.

Just make sure it's a good one ;-)

Of course, the volatility of a concentrated portfolio will be higher, but volatility does not equal risk, even though many finance textbooks will tell you otherwise.

Owning 6 great businesses is less risky, yet offers more upside potential (!), than owning 30 mediocre ones.

Asset allocation

By the way, did you notice that we are only talking about having stocks in your portfolio.

Why?

Well, our goal is to maximize our return on investment, and stocks have historically been the asset class to generate the highest returns over the long-run.

Why invest in something that earns you less than the best possible return on your money?

You'd be cheating yourself.

Also, famous research from Fidelity has shown that dead investors earn the best returns... because they leave their stocks alone, and therefore minimize transaction costs, and maximize their time in the market, instead of timing the market.

Keeping money on the sidelines waiting for the perfect time to get in increases the risk of missing out on significant gains, and has been proven to result in sub-par returns.

So keep that money invested!

Obviously, if you currently have some cash in your portfolio and there are no good deals to be found, then don't just blindly invest it.

Just try not to stay on the sidelines for too long, and when that opportunity finally arises, bet heavily!

Position sizing & the Kelly formula

Now that we know how many stocks we need in our portfolio (six or less), the next question is how much to invest in each of these positions?

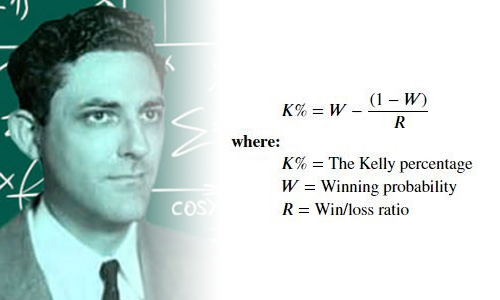

The incredible value investor Mohnish Pabrai popularized the so called Kelly formula in his book The Dhandho Investor as a way to determine optimal position sizes.

That's why you will find numerous articles on the Kelly formula online.

(For more info on the Kelly formula, I recommend reading William Poundstone's book Fortune's Formula)

However, Pabrai himself has in fact stopped using this formula, and even said it was a mistake to include it in his book.

The reason is that the Kelly formula assumes you can repeat your bet unlimited times, while as a long-term investor, the amount of "bets" you'll make in a lifetime is actually very limited.

It also requires you to estimate the odds of a stock making you a profit, which is quite hard to determine with any degree of certainty.

So what then?

Personally, I keep it very simple.

I invest half my money in my two top picks, and the other half in the rest of my stocks.

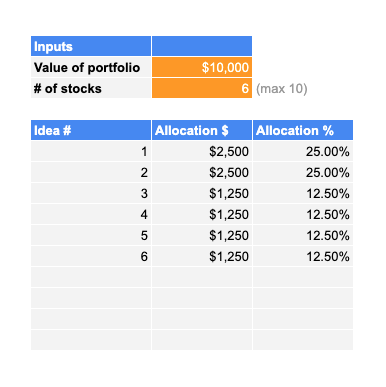

So for a $100K portfolio with 6 stocks, $25K goes into each of my top two stocks, then $12.5K goes into each of the other 4 positions ($100K / 2 / 4).

Is this statistically speaking the "optimal" way to do it?

Probably not, but it is simple to apply and has worked brilliantly for me.

Are there other ways to determine position sizing?

Uh.. yeah, there are tons of ways! To name just a few:

- Variance Optimization

- Conditional Value-at-Risk

- Risk Parity

- Minimize Tracking Error

- Information Ratio

- Sortino Ratio

- Omega Ratio

- Minimize Maximum Drawdown

However, many of these fancy-named methods are heavily based on complex math and questionable assumptions, making them less than ideal for the practical investor.

Portfolio rebalancing

Once you've purchased your six-or-so stocks, prices will obviously move up and down.

As a simplified example, let's assume we have only two stocks in our $10K portfolio.

We invest $5K in stock A, and $5K in stock B.

Stock A doubles in price, so that position is now worth $10K, while the price of stock B remains the same.

Our total portfolio is now valued at $15K, of which $10K, or 66.7%, is invested in stock A.

So while we started with a 50-50 split between the two stocks, the price changes have also changed this balance.

We could consider rebalancing this to bring things back to 50-50.

How?

We sell $2.5K of stock A to bring its market value down to $7.5K, and then invest the proceeds into stock B, if we still believe this stock to be a good investment, of course.

We end up with $7.5K in stock A, and $7.5K in stock B, locking in some of our profits and re-investing them into the still undervalued stock.

This strategy, which is similar to what legendary investor John Templeton suggested, essentially forces you to buy low and sell high, which is obviously what we want.

For small to medium sized portfolios it is more than enough to rebalance once a year.

Free position sizing spreadsheet

To make things a little easier for you, I created a simple, free position sizing spreadsheet.

Download position sizing spreadsheet

Let me know in the comments how you determine how many stocks to buy and how much to invest in each of them!